IT projects: key points

Disclaimer

This section presents (or recalls) the characteristics of IT project management that we consider essential for introducing democratic dialogue into these projects.

This is therefore a presentation of IT project management that is not intended to be technical or exhaustive.

This section is aimed primarily at non-computer specialists.

Impact of the application (project object) on work processes

Needs/requirements

Application design methods: life cycles

Stakeholders in a IT project, committees

Debts that an IT project can generate: technical debt, social debt

Impact of the application (project object) on work processes

An important point for democratic dialogue in the approach to an IT project is to identify at a very early stage whether the future application will be integrated into existing processes (with possible marginal process modifications) or whether its very purpose is to support process re-engineering.

In the latter case, the processes implemented in the application will be the new processes targeted by management (sometimes with the agreement of users), processes which users will have to comply with.

The impact on working conditions and well-being at work will of course not be the same in both cases. The democratic dialogue during the project will have to take this into account.

Needs/requirements

Needs are the origin and basis of any digital IT project.

Needs are defined by the project’s business line manager, the project owner and future users, although the project owner (project manager, architects, developers, etc.) may have to reformulate certain needs, or even write them up (following interviews).

The success of the project, the effectiveness of the application, and also the well-being at work that will be achieved with this software, depend to a large extent on the completeness and precision of the needs expressed.

The requirements are expressed during the first phase of the project (scoping) and refined during the second (design).

Note: in APIDOR, no distinction is made between the terms “need” and “requirement”, which are therefore used interchangeably here, as synonyms.

Functional and non-functional requirements

There are several ways of classifying needs (requirements).

But a distinction is generally made between functional and non-functional requirements.

Functional requirements (FR)

Functional requirements express what the application must do, the services it must render, the functions it must perform: processing it must perform (including the types of interaction with human agents), calculations, data processing, inputs it will receive, their formats and sources (documents, interactions with an agent, inputs from other applications, etc.), outputs it will produce, their formats and media (printed documents, screens, data to be transferred to other applications, etc.), data that must be stored.

The focus here is on the application as a black box, and not on its internal technical operation.

Note: detailed functional requirements are often written by the project manager (and sometimes the same applies to general functional requirements), or by the project owner, but very rarely by the people directly concerned (users of the future application). This is generally the case for the “User stories” in agile approaches (see Democratic dialogue in agile approaches).

Non-functional requirements (NFR)

These are the qualities or properties expected of the application, the conditions (constraints) under which it must operate. They are essential to the success of the application, but are often imprecise and difficult to describe.

There are many types of non-functional requirements.

They generally focus on essentially technical issues such as: security (ability to detect and block intrusions, etc.), reliability (fault tolerance, etc.), performance (response time, etc.), maintenance in operational condition (failure analysis and containment capabilities, etc.), scalability (ability to adapt to changes in the technical environment, etc.), regulatory constraints (standards, national and European regulations, etc.), usability (ease of learning, interface ergonomics, etc.).

The last theme (usability, sometimes referred to as “ergonomics”) is generally not explored in much detail: ease of use, speed of learning required… are mentioned, without these concepts being defined in detail. What does “easy to use” mean, for example, without specifying a time frame? “Easy to use” after one hour, one day… of training? After three months, a year… of use?

The notion of “user experience” (UX)1 aims to go beyond usability by taking into account aspects such as aesthetics, emotion, pleasure, etc. in the user’s interaction with the application. This concept is often used for external users, for example customers purchasing from a web application.

When working conditions are mentioned, it is mainly from the point of view of the risks of errors by users that they could cause. And not, therefore, from the angle of the prevention of health risks, nor of well-being and citizenship at work (see APIDOR’s definition of the latter concept).

It should also be noted that issues such as ethics are rarely considered, and when they are, they generally only refer to compliance with certain standards or regulations (e.g. European GDPR).

Application design methods: life cycles

There are many different approaches, methods, modelling tools, software engineering tools, etc. for designing software.

In APIDOR, the choice has been made not to refer to any particular method. Only a few examples are sometimes given, for illustrative purposes only, without any attempt to be exhaustive or representative.

Design approaches and methods are usually classified according to the project life cycle model they follow (process by which the need is met, list of stages and transition from one stage to another): Waterfall, V, W, Spiral.

Depending on the model followed in the project, the form and key moments of a democratic dialogue may vary.

Project lifecycle vs. application lifecycle

The management of an IT project stops with the deployment of the application (and the first maintenance actions).

It should be noted that the entire lifecycle of the application must also be the subject of structured management, involving the stakeholders concerned (including users and people affected by the application) or their representatives.

Upgrades will be necessary throughout the life of the application, according to a logic that Pierre Caye2 describes as “continuous evolutionary development (…) characteristic of all maintenance operations”.

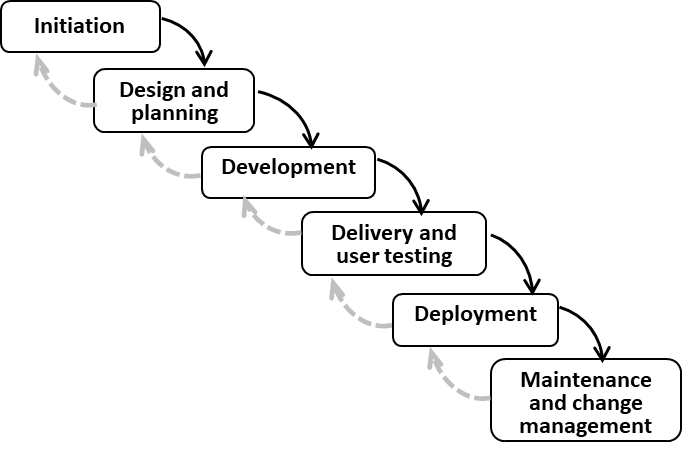

Waterfall model

The cycle is essentially sequential. As soon as a phase is considered complete (a decision taken on the basis of documents or achievements), we move on to the next stage (black arrows).

Backtracking (grey dotted arrows) is only possible from one phase to the one preceding it. This tunnel effect is the essential problem posed by this cycle: for example, a design error (particularly in the understanding of a need) identified in the deployment phase will be very costly to correct because it will be necessary to “go back” three stages in the waterfall. The risk is that errors originating in the earliest phases will not be corrected, or will not be fully corrected.

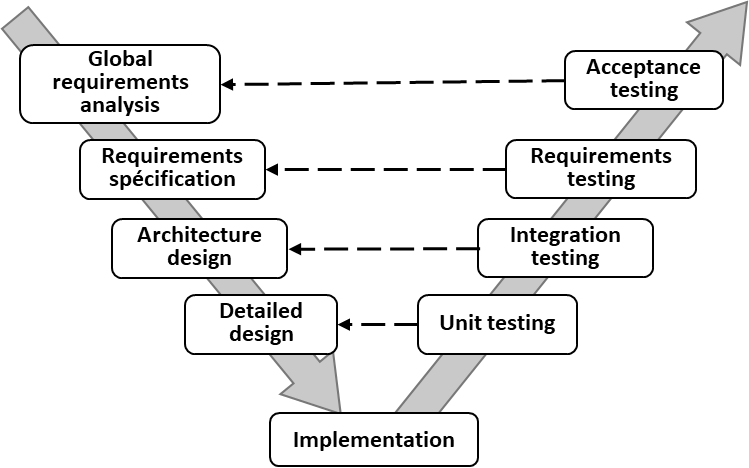

V-model

The V-cycle model (and its W variant) was developed to limit the risk of late error identification. However, this model remains sequential (it is in fact a variant of the waterfall model), and still involves a risk of tunnel effect.

Particular attention is paid here to the verification and validation stages, which are defined in detail.

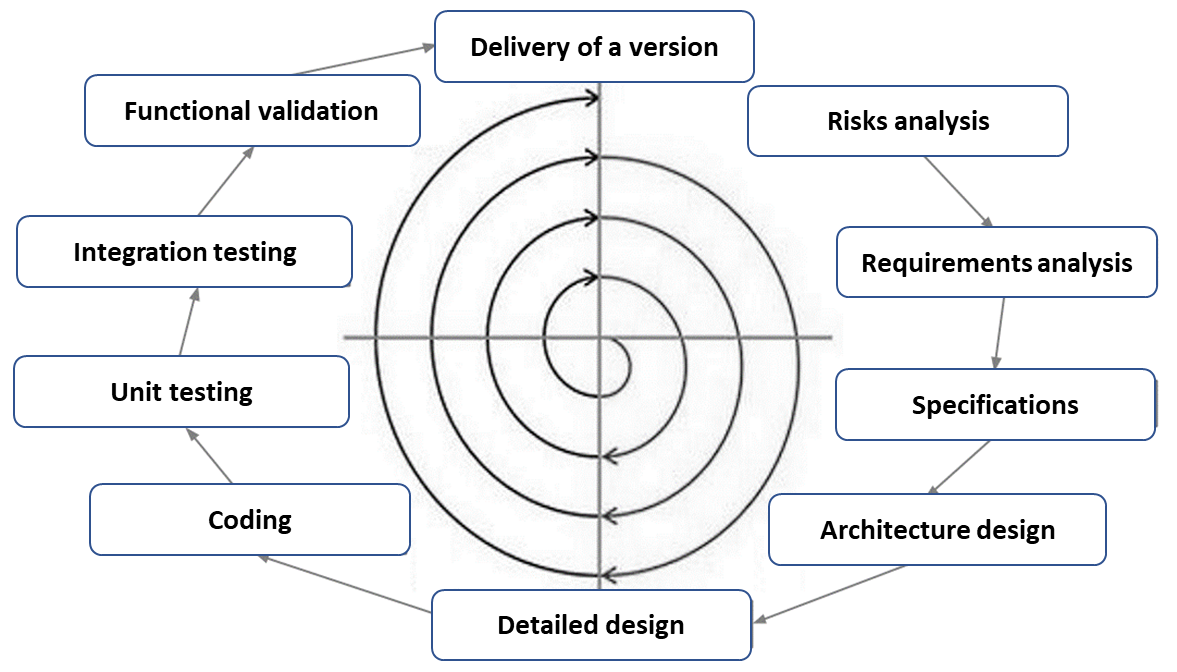

Spiral, iterative and incremental models

These models represent a break with previous models.

Their common principle is a progressive approach to the development of digital information systems, with short cycles enabling frequent deliveries (and validations) throughout the project. Regular feedback from the customer ensures that, from the very first deliveries (very early on in the project), what is delivered meets expectations.

At the root of this approach is the conviction that not all requirements can be expressed in detail at the start of a project. The needs of the customer, of future users, may change during the course of the project (changes in the organisation’s strategy, changes in its economic or regulatory environment, etc.). In addition, the fact that the first versions of the software (or some of its modules) can be used very quickly can give the customer a better understanding of what they can expect from the application, and consequently a change in the way they express their requirements.

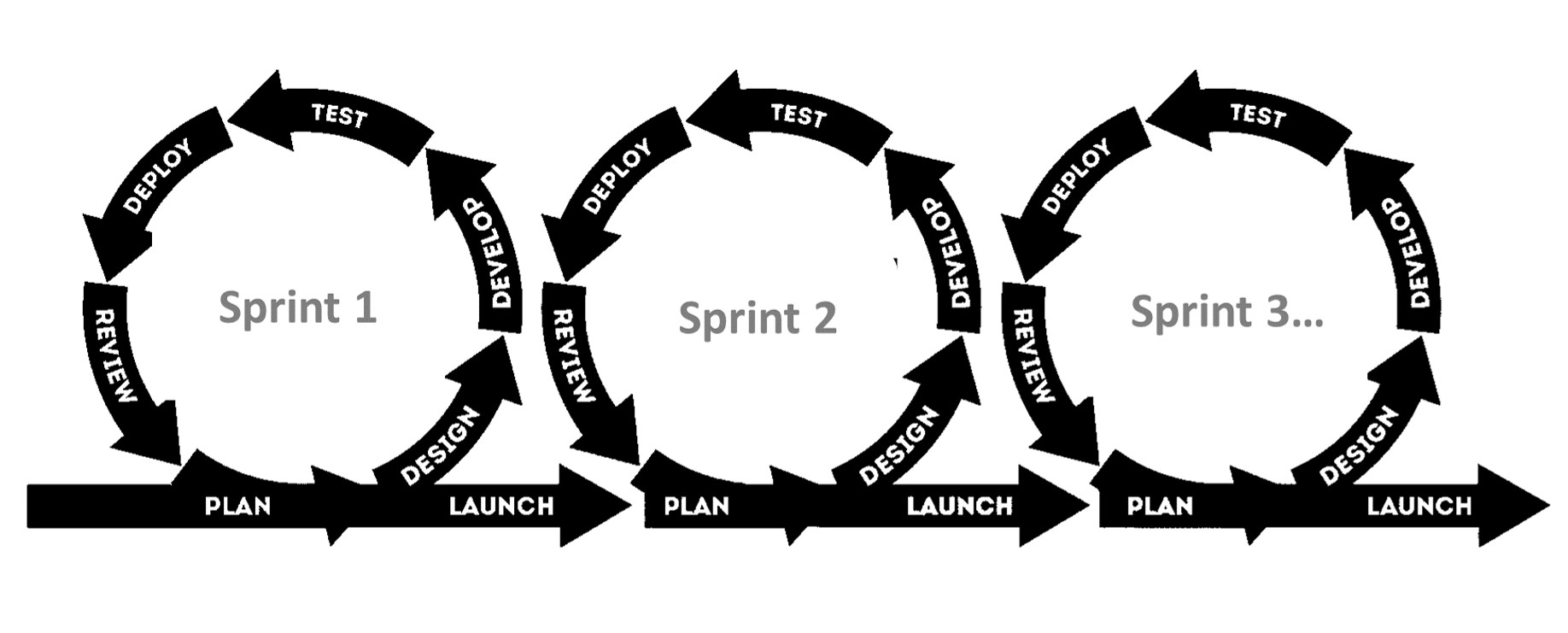

Among the methods that follow this type of cycle, the most widespread are the agile approaches (see Democratic dialogue in agile approaches). There are many of them: DSDM3 , XP4 , Scrum5…

The illustrations given in APIDOR are taken from Scrum.

Note: the spiral cycle can be used in a more or less extensive list of project phases. The whole project can be managed in agile mode, or the cycle can only concern the stages from development onwards (inclusive), with the first two phases (scoping and design) then being carried out upstream in sequential mode. In this second case, we speak of a hybrid approach (or semi-iterative cycle).

Scrum is an iterative, incremental approach that works on the basis of successive sprints. A sprint is an iteration that takes place over a limited period of time (from a few days to a month) and produces a delivery that adds new content (increment) to the application under development. Each sprint ends with a review of the sprint’s progress in order to improve the team’s practices.

IT project stakeholders, Committees

Note on the distinction between project owner (PO) and project manager (PM)

In project management, a distinction is traditionally made between the project owner and the project manager.

The project owner represents the owner of the work (in this case, the digital information system developed), the business needs side. The project owner commissions the work and, at the end of the project, puts the system into operation.

The project manager is responsible for the technical implementation of the application that meets the needs expressed by the client. The project manager is responsible for the technical choices made, for ensuring that the application is implemented correctly and that it meets the needs expressed by the client (functional and non-functional needs).

Project participants

Here we present relatively comprehensive lists of stakeholder types. However, some types of stakeholder may be absent from certain projects, particularly in the case of small projects.

Furthermore, the players and their roles are not always easy to define. Sometimes a player has several roles: funder and sponsor, sponsor and customer, customer and user, business analyst and key user, designer and developer, etc.

All the roles in a project can be outsourced, except that of project leader and funder.

The project owner (business side, needs)

- The project leader (sponsor): the person who initiated the project.

A key player, he or she is responsible for the strategic vision and challenges of the project. They take structural decisions, such as setting objectives, modifying the scope of the project, reallocating the budget, etc. They must approve changes of direction if there are technical problems. They have signing authority over the project (because they has a budget for the project). - The funder: provides the financial resources needed to complete the project. This may be the client, the project manager, more rarely the project owner, or sometimes even external funders.

- The Product Owner (PO): this is generally the client (individual, group or organisation), for whom the software to be developed is intended. With a lower hierarchical level than the pilot, they are present throughout the project, unlike the pilot who is only present at essential moments. They take part in weekly or even more frequent meetings. He must know the business, he is an agent of the business production system (but sometimes he is a consultant).

- The project owner assistant (POA), a functional analyst: present throughout the project, he or she must have business knowledge and experience of IT He or she gathers the requirements of the project owner, in order to lighten the project owner’s workload. They are responsible for translating the requirements into functional specifications for the development team. This is usually an external consultant.

- Business analysts (business analysts, functional experts/consultants, technical-functional experts): either operational or business experts. They play a central role in analysing existing systems, expressing requirements and validating them. Among the business analysts, a functional project manager is sometimes appointed, but this role is often confused with that of the project manager or project owner.

- Specialists in specific subjects that are not related to the business in the strict sense: there are regulations, standards, etc. that will produce requirements that are not related to the business in question. The project manager or project owner (or the head of the department in which the application will be implemented) needs to be aware of these requirements and should therefore call on the services of specialists (legal experts, security manager, etc.).

- Users: future users of the application (and possibly, but much more rarely, people who are affected but not users).

Among users, there are generally several types of role:- end users, who will use the future software in their work

- The project owner can identify (or designate) key users. These are the business referents who will have a more important and regular role in the expression of requirements and acceptance.

- similarly, the project owner may wish to have pilot users who will test the application in advance of the phase.

- Stakeholders (third parties): these are the people, groups or organisations who have a direct or indirect interest in the project, or who will be affected by the application to be

The project management team (the technical side, implementation)

In the case of application development (rather than purchasing off-the-shelf software)

- The technical project manager (the PM): is responsible for organising the team’s work and monitoring implementation.

- The project manager officer (PMO): may be specifically responsible for project planning, coordination and execution. But in many IT projects, when a PMO exists, they concentrate mainly on controlling schedules and costs.

- The development team: designers, developers, engineers with different specialities (programming languages, systems, specific technologies, etc.).

- The architect: carries out the technical analysis needed to draw up the construction plan for software, a network, a database, etc.

- The test manager: designs and implements the test plans, builds or validates the test sets and runs the tests to detect any anomalies.

In support of the project management team, various specialist players may be involved in the project:

- The network administrator: is responsible for managing and maintaining the IT project’s network infrastructure.

- The Security Manager: is responsible for developing, implementing and monitoring the security measures needed to prevent intrusions and data breaches.

- The infrastructure specialist: is responsible for designing, implementing and maintaining the hardware infrastructure required for the IT project.

- The documentation manager: responsible for compiling and managing documentation relating to the project and the application developed (technical documentation, user manuals, etc.).

- A Design Thinking team: partly made up of ergonomists, the team will be looking at the “user experience”1 (UX), the interactions between different users…

Note that in some organisations, certain projects build applications that can be used by internal users (professionals) as well as external users (external customers, end users). The logic is often that the application is developed with the aim that functions performed internally can in the more or less near future be performed solely externally, by the customers or users themselves. The “user experience” is then very close to (if not totally assimilated with) the “customer experience”.

Buying off-the-shelf software

When purchasing software packages, external parties will collaborate with internal parties.

The former will mainly be the publisher of the chosen off-the-shelf software, and generally also an IT services company specializing in this software package (system integrator): sales representatives, business consultants, and technical consultants.

Among the internal players, those responsible for the business side will have a role to play, especially in the case of a complex software package requiring extensive configuration (e.g. an ERP).

In the case of relatively simple software packages (which do not require complex configuration), the IT team may be very small and have little involvement, except in the acceptance, deployment and maintenance stages. But in the case of a complex software package, an IT team will need to work closely with the system integrator company and sometimes also with the software publisher.

Players: specific features of agile approaches (examples from Scrum)

The organisation of teams and roles in agile approaches (in this case Scrum) follows a specific logic, which differs from that of non-agile projects.

There are fewer roles, and each role is often a fusion of different roles from non-agile projects.

Teams are generally more versatile than in sequential projects (waterfall, V or W).

The specific roles are as follows.

- The Product Owner (PO): represents the business side (needs). They validate all decisions concerning the product and the content of the product roadmap. Their role can sometimes also be that of project manager, with the latitude to take strategic decisions on the project.

- The Scrum manager (SM): they are primarily responsible for the methodology used, and assist the teams in using the Scrum components (events, artefacts, etc.). They are sometimes likened to the project manager, but this role can also be held by the PO.

- The development team: the role of implementing the technical The members of the team are responsible for the increment, the sprint log and therefore for the way in which the application will be produced. They may also be responsible for estimating the workload and completion time for each item.

The PO, the SM and the development team make up the Scrum Team. This team works on the project alongside the other stakeholders: the Sponsor (client), who initiates the project, the Funder (when different from the Sponsor), who provides financial support for the project, and the users for whom the application is intended. The latter play an essential role in validating and guiding the decisions that will be taken regarding the application’s functionalities.

Committees

A number of committees are generally involved in the governance of an IT project.

Here are the main committees.

Strategic committee (sponsor committee)

It decides on strategy changes. If the project needs to evolve, it takes decisions to reduce the risk.

It meets mainly at the start of the project (initiation phase) and at the very end, when strategic decisions are required.

Steering committee

This is the decision-making body (except for strategy changes, which are the responsibility of the Strategic committee).

It is made up mainly of the business players, and includes the client or their representative, the project owner, the project owner’s assistant or the functional project manager, the business players in the main areas (+ any ancillary areas), and the project manager.

It monitors the progress of the project against the initial schedule, the actual costs against the initial budget, any changes in risks, etc.

He makes decisions on the method of implementation (off-the-shelf software purchase or development), on the progress of the project (validating the transition from one stage to another), validates deliveries, and makes decisions on planning and resource allocation.

It lists the points requiring decisions at the Strategic committee level.

Frequency: during the upstream phases, the Steering committee may meet once a week or once every two weeks. Thereafter, meetings are held much less frequently, except for urgent matters.

Comité de projet (COPRO, comité de suivi)

Traite des questions opérationnelles (du suivi opérationnel) au sens large.

Il comprend le MOA et/ou l’assistance à MOA, le chef de projet technique, éventuellement des membres de l’équipe de la MOE et des utilisateurs-clés.

Il suit l’avancement du projet au niveau opérationnel, et se centre principalement sur le périmètre du projet et ses livrables. Pour l’équipe de la MOE, il peut être un lieu d’échanges sur les difficultés rencontrées et favoriser un partage d’expérience.

Il liste les points demandant des décisions au niveau du COPIL.

Périodicité : hebdomadaire, voire plus fréquent dans des moments particuliers.

Project committee (monitoring committee)

Deals with operational issues (operational monitoring) in the broadest sense.

It includes the project owner and/or the project owner’s assistant, the technical project manager, and possibly members of the development team and key users.

It monitors the progress of the project at the operational level, focusing mainly on the project scope and its deliverables. For the project management team, it can provide a forum for discussing any difficulties encountered and encouraging the sharing of experience.

It lists the points requiring decisions at Steering committee level.

Frequency: weekly, or more frequently at special times.

User Committee

This body is far from being present in all projects.

Its composition is generally decided by the project owner and the director of the department in which the software will be implemented. Users with strong business skills will be appointed. It is not really intended that the composition of the committee should reflect the diversity of future users.

It includes key users, who will be involved in certain phases of the project (in particular the analysis of the existing system and requirements, acceptance). In the case of agile approaches, they may be called upon during development.

The role of the user committee is also to promote the project, and then the application, within the recipient department.

The debts that can be generated by an IT project

Technical debt

“In software development and other information technology fields, technical debt (also known as design debt or code debt) refers to the implied cost of additional work in the future resulting from choosing an expedient solution over a more robust one. While technical debt can accelerate development in the short term, it may increase future costs and complexity if left unresolved.”6

Note: the ‘problems’ referred to in this definition can have a major impact on the quality of working life, and can require users of the software concerned to make much greater efforts to maintain the level of efficiency demanded by management.

It should be noted that a technical debt can also arise in the case of the purchase of off-the- shelf software chosen because it is less expensive, but which proves to be ill-suited and should subsequently be changed (but not without the software having generated all kinds of problems in working conditions).

Social debt

The impact of an IT application on the well-being of the organisation’s employees must be fully taken into account during the project.

Ignoring these impacts, not considering democratic dialogue as a factor in the success of the IT project (on the pretext of efficiency and speed), will very probably lead to the creation of what we call a “social debt”.

By “social debt” we mean a deterioration in well-being at work (including health), a loss of citizenship at work (total or partial) generated by the use of the new software.

APIDOR’s hypothesis is that the existence of a significant social debt, like that of a significant technical debt, is likely to degrade the organisation’s performance.

Notes & references

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/User_experience

- Caye P. (2020) Durer. Éléments pour la transformation du système productif, Les Belles Lettres.

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dynamic_systems_development_method

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Extreme_programming

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scrum_(software_development)

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Technical_debt